#AcWriMo 2025

This year, I’m working through Nathalie Tasler’s prompts. I'll keep updating this post as the month goes on.

Day 9

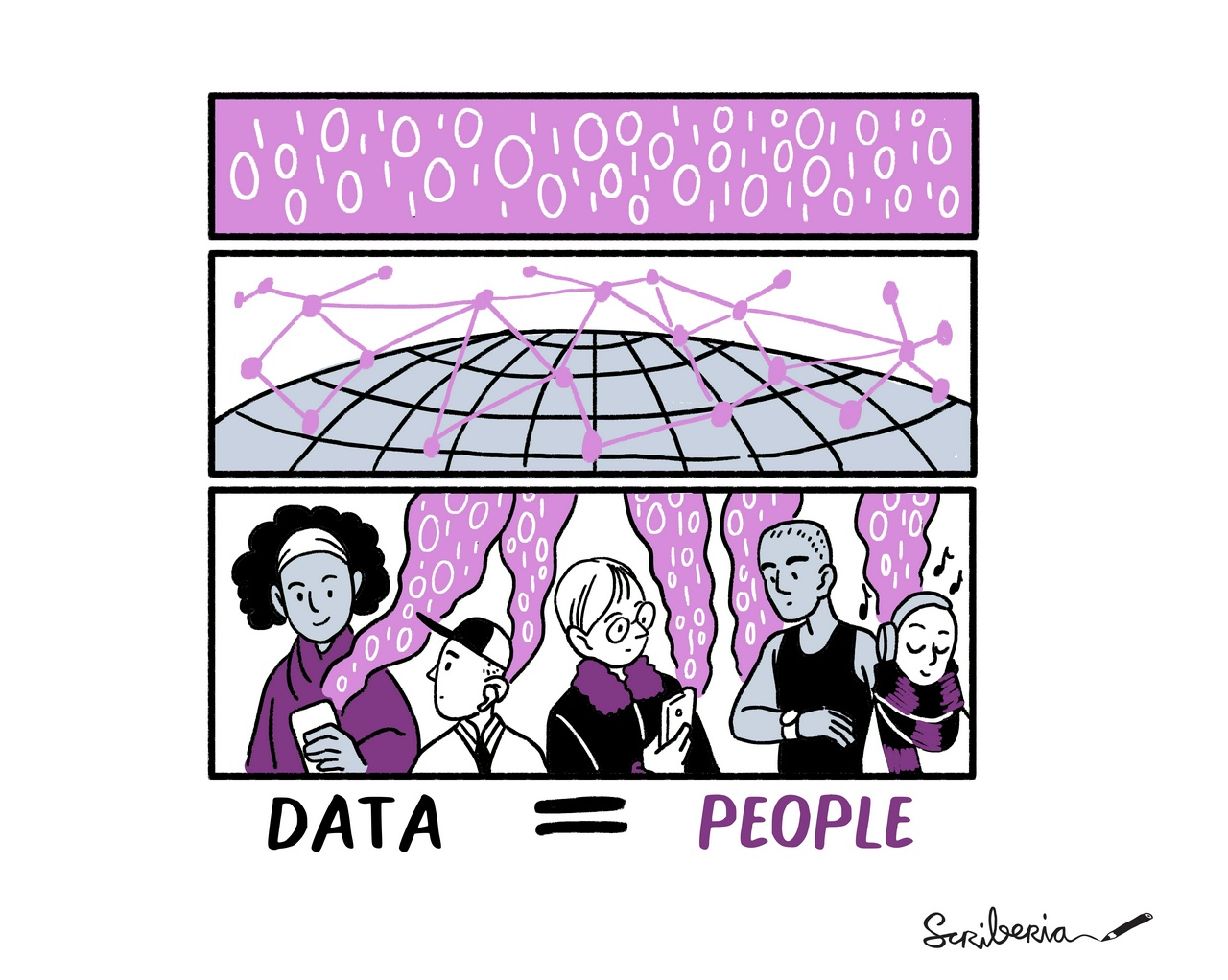

Cheating a little here, with  from the Scriberia illustrations commissioned during a Turing Way book dash, back when I was in the very early stage of thinking about this idea.

from the Scriberia illustrations commissioned during a Turing Way book dash, back when I was in the very early stage of thinking about this idea.

Day 8

Mastodon: I'm writing a book about how different people are—and are not—represented in different data sets. In particular, it's about how the ways that different actors collect data exclude or misrepresent people who are in some way out of the mainstream: because of their #gender, their way of life, their identity/ies.

LinkedIn: My current book project focuses on exclusion and misrepresentation in data sets. When we collect data about people, the information that we choose to collect is a choice: and not everyone fits neatly into predefined categories.

Day 7

I have a tendency to ramble in my writing, and to use a lot of run-on sentences. I'd like to get better at writing more concisely—and at editing my own writing.

Day 6

I don't take as much care of my readers as I should: at least, not in academic writing. Sometimes this is because I'm racing to meet a deadline and 'done' is better than 'perfect,' sometimes it's because I'm so fed up of a paper that I just want shot of it. And sometimes it's because I feel pressure to 'perform' academic inscrutability. I'm trying to move away from that—my book project idea is for a general reader—but it does creep in, especially when I've been reading a lot of academic literature that tends towards the pompous or the jargon-y.

Day 5

A possible abstract for a paper or conference submission:

Missing drafts Machine learning—including generative AI—relies on training data, whether it is in the form of structured data, unstructured text, or images. But this data didn't spring into existence fully-formed as a .html, .txt or .csv file. This paper will make visible the information and thought that went into creating the training data that is used to build machine learning, large language and image generation models. From court case submissions that are used in crafting the final judgement produced by a judge, to tried-and-failed experiments which never produce academic papers, to the previous drafts of novels which exist only on the writer's computer: this paper will show how this hidden information is vital to understanding how training data was created, and therefore to understanding the performance of machine learning models.

Day 4

To write, I need quiet, a door that closes, to be left alone. I need to spend time settling in to the work, to pick up where I left off before, and to quiet my brain from the day-to-day.

This isn't always feasible! But it's easier to come by in the afternoons.

Day 3

Weakness: sometimes it is useful to spend time looking for a reference! Future Laura isn't always grateful when Past Laura leaves her with all the work to do. Sometimes looking for the reference helps me realise that the point I was trying to make isn't actually that useful or relevant.

Strength: when I am writing well, I am able to put a lot of words down—and it's always easier to edit existing text than come up with it in the first place.

Day 2

When I am writing at my best, I am like a well-oiled machine: the words flow easily from my brain through my fingers and on to the screen. I don't get bogged down in looking for the perfect reference or exploring a footnote – I simply note where these are needed and keep going.

Day 1

I'm hoping to use these prompts to help me think through my current book project!